-

This is a political forum that is non-biased/non-partisan and treats every person's position on topics equally. This debate forum is not aligned to any political party. In today's politics, many ideas are split between and even within all the political parties. Often we find ourselves agreeing on one platform but some topics break our mold. We are here to discuss them in a civil political debate. If this is your first visit to our political forums, be sure to check out the RULES. Registering for debate politics is necessary before posting. Register today to participate - it's free!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

How does black America get fixed?

- Thread starter T25

- Start date

- Joined

- Dec 22, 2012

- Messages

- 80,340

- Reaction score

- 27,385

- Location

- Portlandia

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Libertarian - Right

I can't answer that question. I would offend all the snowflakes from my lack of political correctness. To correct it however is not "law and order," of which this thread in in.

- Joined

- Nov 18, 2016

- Messages

- 61,263

- Reaction score

- 38,437

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Liberal

What can be done?

The same way Appalachia can be fixed: investment in socioeconomic development:

“ A woman who escaped her drug-addled hometown in rural Kentucky said Appalachia residents face similar problems as inner-city Black communities but get much less attention.

"Some of the poor Black communities, if something happens over there — I don't know if it's a skin color thing, I don't know if it's to try to maybe shine a negative light on their communities — but they do report more on these instances," Melissa Smith told Fox News. "Whereas in our communities, I've never heard anybody on the media even utter the word 'Appalachia.'"”

'Ignored' Appalachia faces similar issues as inner-city Black areas: 'Nobody talks about it,' says KY woman | Fox News

Rampant drug use, crime and lack of opportunities forced Appalachian woman to leave her hometown

Addressing Substance Use Disorder in Appalachia - Appalachian Regional Commission

The nation’s substance use disorder crisis disproportionately impacts Appalachia, where in 2022 overdose-related mortality rates for people ages 25–54 was 64 percent higher than the rest of the country. Appalachians struggling with substance use disorder encounter additional barriers including...

- Joined

- Dec 22, 2012

- Messages

- 80,340

- Reaction score

- 27,385

- Location

- Portlandia

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Libertarian - Right

The problem is people want to make it a race issue, and it isn't in the regards to economics. Generational resentment adds to the equation.The same way Appalachia can be fixed: investment in socioeconomic development:

“ A woman who escaped her drug-addled hometown in rural Kentucky said Appalachia residents face similar problems as inner-city Black communities but get much less attention.

"Some of the poor Black communities, if something happens over there — I don't know if it's a skin color thing, I don't know if it's to try to maybe shine a negative light on their communities — but they do report more on these instances," Melissa Smith told Fox News. "Whereas in our communities, I've never heard anybody on the media even utter the word 'Appalachia.'"”

'Ignored' Appalachia faces similar issues as inner-city Black areas: 'Nobody talks about it,' says KY woman | Fox News

Rampant drug use, crime and lack of opportunities forced Appalachian woman to leave her hometownwww.foxnews.com

Addressing Substance Use Disorder in Appalachia - Appalachian Regional Commission

The nation’s substance use disorder crisis disproportionately impacts Appalachia, where in 2022 overdose-related mortality rates for people ages 25–54 was 64 percent higher than the rest of the country. Appalachians struggling with substance use disorder encounter additional barriers including...www.arc.gov

- Joined

- Nov 18, 2016

- Messages

- 61,263

- Reaction score

- 38,437

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Liberal

The problem is people want to make it a race issue, and it isn't in the regards to economics. Generational resentment adds to the equation.

LOL, The OP title is literally “ How does black America get fixed?”- not “how does poverty get fixed”.

This is clearly a racial issue.

- Joined

- Dec 22, 2012

- Messages

- 80,340

- Reaction score

- 27,385

- Location

- Portlandia

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Libertarian - Right

Do you think poverty isn't part of the equation?LOL, The OP title is literally “ How does black America get fixed?”- not “how does poverty get fixed”.

- Joined

- Nov 18, 2016

- Messages

- 61,263

- Reaction score

- 38,437

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Liberal

Do you think poverty isn't part of the equation?

I think it’s all about poverty. But that’s not the OP topic, is it?

So why don’t you ask that from the person who started the OP? Ask them to change the title and then we can talk.

But we both know that’s not what’s really bothering the OP. They are not really interested in the topic of poverty.

- Joined

- Aug 6, 2019

- Messages

- 21,247

- Reaction score

- 9,365

- Location

- Bridgeport, CT

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Libertarian - Right

The same way Appalachia can be fixed: investment in socioeconomic development:

“ A woman who escaped her drug-addled hometown in rural Kentucky said Appalachia residents face similar problems as inner-city Black communities but get much less attention.

"Some of the poor Black communities, if something happens over there — I don't know if it's a skin color thing, I don't know if it's to try to maybe shine a negative light on their communities — but they do report more on these instances," Melissa Smith told Fox News. "Whereas in our communities, I've never heard anybody on the media even utter the word 'Appalachia.'"”

'Ignored' Appalachia faces similar issues as inner-city Black areas: 'Nobody talks about it,' says KY woman | Fox News

Rampant drug use, crime and lack of opportunities forced Appalachian woman to leave her hometownwww.foxnews.com

Addressing Substance Use Disorder in Appalachia - Appalachian Regional Commission

The nation’s substance use disorder crisis disproportionately impacts Appalachia, where in 2022 overdose-related mortality rates for people ages 25–54 was 64 percent higher than the rest of the country. Appalachians struggling with substance use disorder encounter additional barriers including...www.arc.gov

Sure, but the violent crime rate of appalachia is below the national average.

- Joined

- Aug 6, 2019

- Messages

- 21,247

- Reaction score

- 9,365

- Location

- Bridgeport, CT

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Libertarian - Right

I think it’s all about poverty.

It's not. There are places all over the world that are dirt poor and have low crime rates.

- Joined

- Nov 18, 2016

- Messages

- 61,263

- Reaction score

- 38,437

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Liberal

Sure, but the violent crime rate of appalachia is below the national average.

“ I have been seeing a ton of people lately (not here really) trying to use Appalachia and it’s people as some sort of conservative rallying call. This idea of noble poverty is rearing it’s ugly head. It’s been done a million times over but I just have some faith that the new generation recognizes this bullshit.

There’s nothing noble about the systemic oppression our region faced, there’s nothing to be saved with mythic idealization of mountain folk as, essentially, “coal dwarves” like some weird Tolkien bullshit. I absolutely can’t stand it.

I’ve seen more and more lately something like this: “harumph, hmm, well if poverty leads to crime and violence, how come West Virginia doesn’t have nearly as much as inner-city Chicago, grumble grumble”

No shit! The population density of the communities isn’t comparable for one, and two, the way the communities are structured is completely different. If you took the entire state population of WV and put it in ****ing Wyoming County, you’d have the same rate of murder and violent crimes.

We, as an actual regional culture in America, have been marginalized, stolen from and used a political tool for hundreds of years at this point. My upbringing is a lot closer to inner-city Chicago than some hillbilly myth.

Don’t let them separate you from your actual brothers and sisters. Don’t let them speak for you or our region or our culture. We are not simple folk happily existing within the subjugation of the American government.”

- Joined

- Aug 6, 2019

- Messages

- 21,247

- Reaction score

- 9,365

- Location

- Bridgeport, CT

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Libertarian - Right

Thomas Sowell makes a solid argument that the villain is the progressive welfare state. He has a lot of evidence that blacks were improving by income and education until the great society programs of the 60s, and then it all went downhill from there.

- Joined

- Jan 8, 2010

- Messages

- 84,173

- Reaction score

- 76,933

- Location

- NE Ohio

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Liberal

Step 1. Don't have society destroy their wealth every generation with stuff like the Tulsa massacre. redlining, or encouragement to get subprime loans.

- Joined

- Jan 15, 2016

- Messages

- 10,792

- Reaction score

- 6,846

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Libertarian - Right

First essential step; abandon the false notion that our species, Homo Sapiens, is divided into distinct 'races'. This erroneous theory, long since disproved, has afflicted the USA since its foundation.

- Joined

- Aug 6, 2019

- Messages

- 21,247

- Reaction score

- 9,365

- Location

- Bridgeport, CT

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Libertarian - Right

Step 1. Don't have society destroy their wealth every generation with stuff like the Tulsa massacre. redlining, or encouragement to get subprime loans.

Created and institutionalized by the new deal.

- Joined

- Nov 18, 2016

- Messages

- 61,263

- Reaction score

- 38,437

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Liberal

Thomas Sowell makes a solid argument that the villain is the progressive welfare state. He has a lot of evidence that blacks were improving by income and education until the great society programs of the 60s, and then it all went downhill from there.

Here is what actually happened to black communities which were improving by income and education:

This is not about something about economic concerns. FDR’s New Deal lifted most of the country out of poverty in the 1930s. But not blacks.

The New Deal Made America's Racial Inequality Worse. We Can't Make the Same Mistake With Covid-19 Economic Crisis.

The Covid-19 pandemic has already caused a level of economic devastation in America that can only be compared to the Great Depression. So it's not

www.rockefellerfoundation.org

This is not about government investment in its people not working. It clearly does- as shown by the rest of the developed and developing world. It’s really about racism.

The conservative approach: weaken government to prove it doesn’t work. Keep blacks in Poverty to prove that black poverty can’t be fixed and is some genetic, innate inferiority- so they just deserve to be left to die off like some social Darwinism freedom of the jungle kind of $hit- and advance plutocracy in the name of “freedom”.

Come on. Admit it. That’s what the OP here is really about.

This is not personal opinion. Just ask senior GOP political strategists, like Reagan’s chief campaign advisor.

“ Atwater: As to the whole Southern strategy that Harry Dent and others put together in 1968, opposition to the Voting Rights Act would have been a central part of keeping the South. Now [Reagan] doesn't have to do that. All you have to do to keep the South is for Reagan to run in place on the issues he's campaigned on since 1964 [...] and that's fiscal conservatism, balancing the budget, cut taxes, you know, the whole cluster...

Questioner: But the fact is, isn't it, that Reagan does get to the Wallace voter and to the racist side of the Wallace voter by doing away with legal services, by cutting down on food stamps?

Atwater: Y'all don't quote me on this. You start out in 1954 by saying, "Nigger, nigger, nigger." By 1968 you can't say "nigger"—that hurts you. Backfires. So you say stuff like forced busing, states' rights and all that stuff. You're getting so abstract now [that] you're talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you're talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is [that] blacks get hurt worse than whites. And subconsciously maybe that is part of it. I'm not saying that. But I'm saying that if it is getting that abstract, and that coded, that we are doing away with the racial problem one way or the other. You follow me—because obviously sitting around saying, "We want to cut this," is much more abstract than even the busing thing, and a hell of a lot more abstract than "Nigger, nigger."”

Southern strategy - Wikipedia

- Joined

- Nov 18, 2016

- Messages

- 61,263

- Reaction score

- 38,437

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Liberal

Created and institutionalized by the new deal.

Yes- the fact that the New Deal was delivered only to whites and ended up only helping them is proof it didn’t work.

Conservative “logic”.

- Joined

- Jan 8, 2010

- Messages

- 84,173

- Reaction score

- 76,933

- Location

- NE Ohio

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Liberal

We had balance and a good institutional norm for decades between then and now. That's not it.Created and institutionalized by the new deal.

- Joined

- Aug 6, 2019

- Messages

- 21,247

- Reaction score

- 9,365

- Location

- Bridgeport, CT

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Libertarian - Right

FDR’s New Deal lifted most of the country out of poverty in the 1930s.

This is totally false. Unemployment was sky high even after years of new deal programs.

But not blacks.

The progressive movement was a racist movement.

- Joined

- Aug 6, 2019

- Messages

- 21,247

- Reaction score

- 9,365

- Location

- Bridgeport, CT

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Libertarian - Right

Yes- the fact that the New Deal was delivered only to whites and ended up only helping them is proof it didn’t work.

Conservative “logic”.

You're logic is if I, as a politician, take your money from you by force, and then spend it the way I see fit, that makes you better off.

- Joined

- Nov 18, 2016

- Messages

- 61,263

- Reaction score

- 38,437

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Liberal

The New Deal did a lot, and we are still benefitting from it- from rural electrification, to the GI bill, to banking reforms, to Wall Street regulations. But by itself, it was not enough. What it took was the war economy of WWII to end the depression. Talk about big goverment spending!This is totally false. Unemployment was sky high even after years of new deal programs.

The progressive movement was a racist movement.

Yes, it was primarily directed towards whites, and therefore primarily helped them, not blacks.

And your conclusion from that is that it didn't help those to whom it was directed?

Last edited:

- Joined

- Nov 18, 2016

- Messages

- 61,263

- Reaction score

- 38,437

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Liberal

That's not logic. That's just the universal experience of all developed and developing economies, from around the world, over the last 2 centuries.You're logic is if I, as a politician, take your money from you by force, and then spend it the way I see fit, that makes you better off.

The Marshall Plan and Postwar Economic Recovery

The Marshall Plan was a massive commitment to European recovery after World War II that was largely supported by Americans.

China’s Education Spending Surge: A Catalyst for Economic Transformation

China’s public education system has undergone significant transformation since its inception in 1949, shaped by historical events and policy decisions. The evolution of education in China reflects…

Unveiling the Secrets: How Finland's Education System is Funded

Discover how Finland's education system is funded and why it stands out globally in promoting equity and high educational outcomes.

kidslearningguide.com

kidslearningguide.com

Last edited:

- Joined

- Oct 7, 2011

- Messages

- 7,360

- Reaction score

- 4,377

- Location

- UK

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Independent

Don't have a "black America" but just an "America"?What can be done?

- Joined

- Jan 15, 2016

- Messages

- 10,792

- Reaction score

- 6,846

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Libertarian - Right

What lifted most of the USA out of poverty was WWII. Britain spent every penny it had in buying US weapons, ships and planes in 1940 and 41. Much to the benefit of US shipyards and factories.This is totally false. Unemployment was sky high even after years of new deal programs.

The progressive movement was a racist movement.

- Joined

- Sep 15, 2012

- Messages

- 38,475

- Reaction score

- 14,353

- Location

- Columbus, OH

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Moderate

The problem is a consequence of the disintegration of moral values, devaluation of education, and breakdown of the family unit. None of that can be fixed from the outside in.What can be done?

- Joined

- Nov 18, 2016

- Messages

- 61,263

- Reaction score

- 38,437

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Liberal

The problem is a consequence of the disintegration of moral values, devaluation of education, and breakdown of the family unit. None of that can be fixed from the outside in.

It can. When people argue that poverty among Black Americans is just due to bad personal decisions—like not finishing school or having children young—they often ignore a crucial fact: personal choices don’t happen in a vacuum. Every personal decision is shaped by a wider context—historical, social, and economic. To focus solely on individual responsibility without looking at broader social/historical/structural conditions is both misleading and unfair.

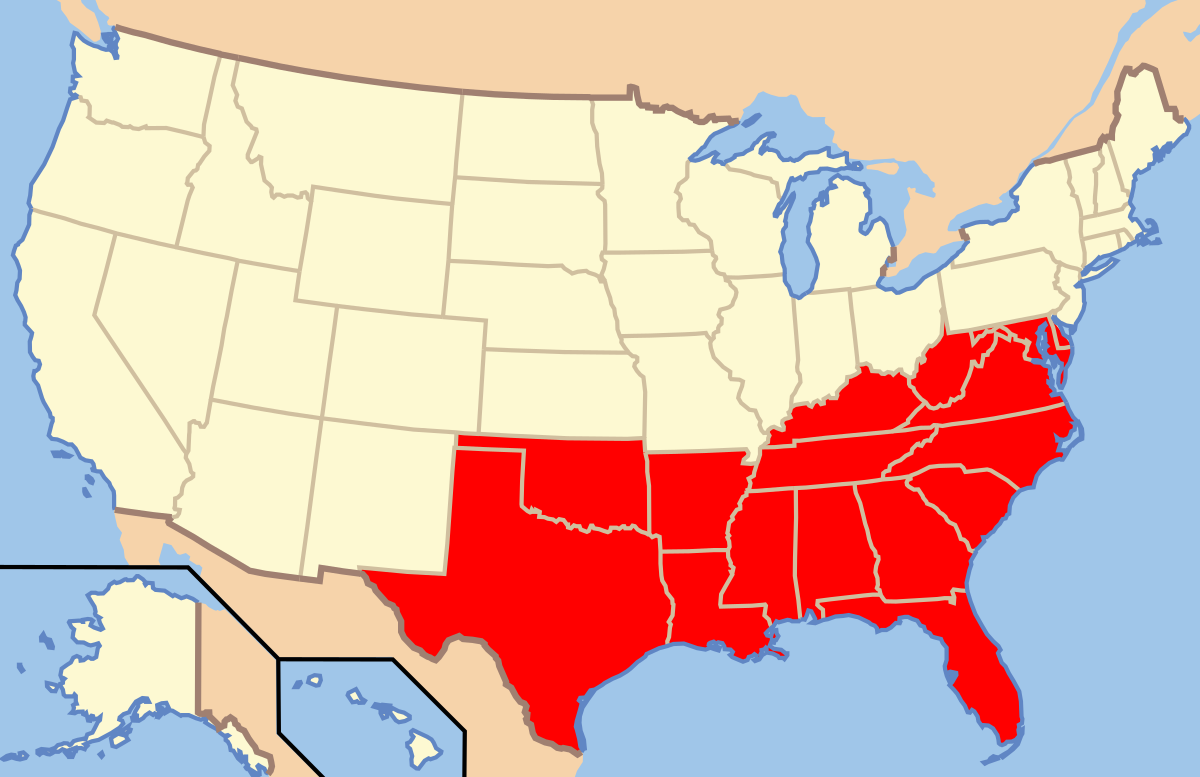

And this isn’t unique to Black Americans. Poor white communities in places like Appalachia also experience high dropout rates, early pregnancy, addiction, and economic stagnation. But the difference is: we don’t usually attribute their struggles to personal failings—we talk about job loss, declining industries, and healthcare gaps. Native American reservations show similar patterns, rooted in centuries of colonization, forced relocation, and broken treaties. These examples prove the point: bad decisions are often symptoms, not causes.

Even historically, groups like the Irish and Italians were once seen as inherently dysfunctional and genetially incapable of self-governance or functional society. They lived in generational poverty, faced discrimination, and were accused of moral failure. But over time, as policies changed and access to opportunity improved, those groups entered the middle class—not because their culture or genetics transformed, but because their context did.

Black communities in the U.S. have faced generations of systemic barriers: slavery, segregation, redlining, underfunded schools, and mass incarceration. These aren’t distant historical events—they shape the present. In much of the country, they weren't even allowed to vote until only a few decades ago. Mid-20th-century redlining policies excluded Black families from home loans, while white families built wealth through subsidized homeownership. This led to today’s massive racial wealth gap. Families who were locked out of that opportunity passed down poverty, not because they made worse decisions, but because the system denied them access to upward mobility.

Ditto for education. Public schools are funded by local property taxes, which means schools in low-income neighborhoods—often predominantly Black—are underfunded and overcrowded. They may lack basic resources, experienced teachers, or safe environments. A student who drops out in this context isn’t necessarily making a "bad" decision—they may be reacting to trauma, needing to support their family, or simply not seeing any payoff from staying in a broken system.

The criminal justice system adds another layer. Black Americans are arrested and incarcerated at much higher rates for offenses like drug possession, even though drug use is similar across racial groups. A felony record can close the door to jobs, housing, and education. When entire communities are policed this way, the cycle of poverty becomes nearly impossible to escape.

So what we call a “bad decision” is not done in a complete vacuum, and often depends on who makes it and under what conditions. A wealthy teen who experiments with drugs or struggles in school often gets second chances. A poor teen making the same choice might face jail, dropout, or lifelong setbacks. The problem isn’t just the decision—it’s the lack of support and safety nets from their broader society that determine the outcome.

This doesn’t mean personal responsibility doesn’t matter—it does. But responsibility is shaped by possibility. When we ignore the role of structure, we hold people accountable for outcomes they never had a fair shot at avoiding.

If we’re serious about solving poverty, and truly want people to make better choices, rather than just perpetuating racism, we need to address not just the choices people make—but the conditions that shape those choices.