- Joined

- Nov 18, 2016

- Messages

- 61,230

- Reaction score

- 38,400

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Liberal

Aaaah... candle light dinners by the Seine, with the crescent moonlight shining bright from behind the Eiffel tower. Standing under the window of your beloved and pining for even a quick glimpse of her sillhouette from the window, the heartache, the longing, the unrequited love... It seems the French created the concept of romance, no?

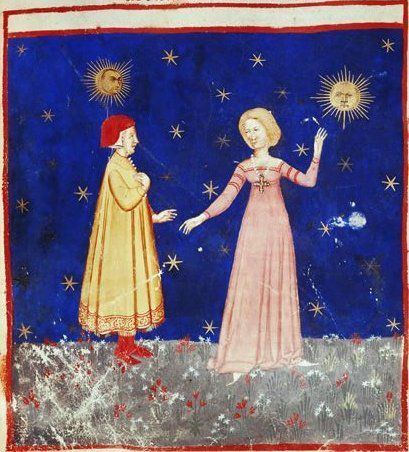

Well, yes and no. I was reading about the history of the concept of romance- and in Europe, at least, it does seem to have started over in France, around the medieval period. That time, especially after the 13th century, saw the introduction of a lot of romantic poetry and literature in Europe. Before that, it seems the concept really didn't exist. Specifically, it seems the concept started with the idea of "courtly love" and "chivalry", traced back to the French troubadours- the poets and musicians of the time. The term "courtly love" appears in only one extant source: Provençal cortez amors in a late 12th-century poem by Peire d'Alvernhe.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

But when you trace the history back even further, it seems the concept was brought to France from the middle east- through the European interactions with the middle east in the Crusades, as well as through Spain from the Moors. A few centuries before the troubadors, the middle easterners had started writing stories which would define romance for the first time. It seems this started around the 9th century- with stories like Layla and Majnun.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

The origins of romance in the Middle East are deeply intertwined with the region's rich literary and cultural history, particularly through the development of Arabic and Persian love poetry and narratives. These traditions, often exploring themes of passionate, unrequited, and even mystical love, have significantly influenced both the region's own cultural landscape and, through various historical exchanges, Western literary traditions. Eventually, this idea of romantic love being intertwined with divine love for God, or used as a metaphor, were explored by Sufi mystic poets like Rumi.

Why did I start this thread? I dunno. I just never equated the middle east with the origins of the concept of romance, of all things. Just found it surprising. Anyone else have insights on this history?

Well, yes and no. I was reading about the history of the concept of romance- and in Europe, at least, it does seem to have started over in France, around the medieval period. That time, especially after the 13th century, saw the introduction of a lot of romantic poetry and literature in Europe. Before that, it seems the concept really didn't exist. Specifically, it seems the concept started with the idea of "courtly love" and "chivalry", traced back to the French troubadours- the poets and musicians of the time. The term "courtly love" appears in only one extant source: Provençal cortez amors in a late 12th-century poem by Peire d'Alvernhe.

Courtly love - Wikipedia

But when you trace the history back even further, it seems the concept was brought to France from the middle east- through the European interactions with the middle east in the Crusades, as well as through Spain from the Moors. A few centuries before the troubadors, the middle easterners had started writing stories which would define romance for the first time. It seems this started around the 9th century- with stories like Layla and Majnun.

Layla and Majnun - Wikipedia

The origins of romance in the Middle East are deeply intertwined with the region's rich literary and cultural history, particularly through the development of Arabic and Persian love poetry and narratives. These traditions, often exploring themes of passionate, unrequited, and even mystical love, have significantly influenced both the region's own cultural landscape and, through various historical exchanges, Western literary traditions. Eventually, this idea of romantic love being intertwined with divine love for God, or used as a metaphor, were explored by Sufi mystic poets like Rumi.

- Arabic Love Poetry:

Arabic poetry, flourishing since pre-Islamic times, is filled with tales of love, longing, and loss. The concept of ishq (passionate, all-consuming love) and hubb (general love) are central themes, often expressed through vivid imagery and metaphors.

- Persian Romance:

The Persian literary tradition, particularly from the 10th century onwards, features epic romances like Vis o Ramin, which explore themes of love, loyalty, and tragedy. These narratives, often set in royal courts, feature complex characters and intricate plots.

- Influence of Sufism:

Sufi mystical poetry and philosophy often use the language of romantic love to express a believer's relationship with God, emphasizing themes of divine love and spiritual yearning.

- Cultural Exchange:

The Islamic Golden Age saw significant cultural exchange between the Middle East and other regions, including Europe. This exchange influenced the development of courtly love traditions in Europe, particularly through the spread of Arabic and Persian literary forms and themes.

Why did I start this thread? I dunno. I just never equated the middle east with the origins of the concept of romance, of all things. Just found it surprising. Anyone else have insights on this history?

Last edited: