- Joined

- Jan 2, 2006

- Messages

- 28,173

- Reaction score

- 14,269

- Location

- Boca

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Independent

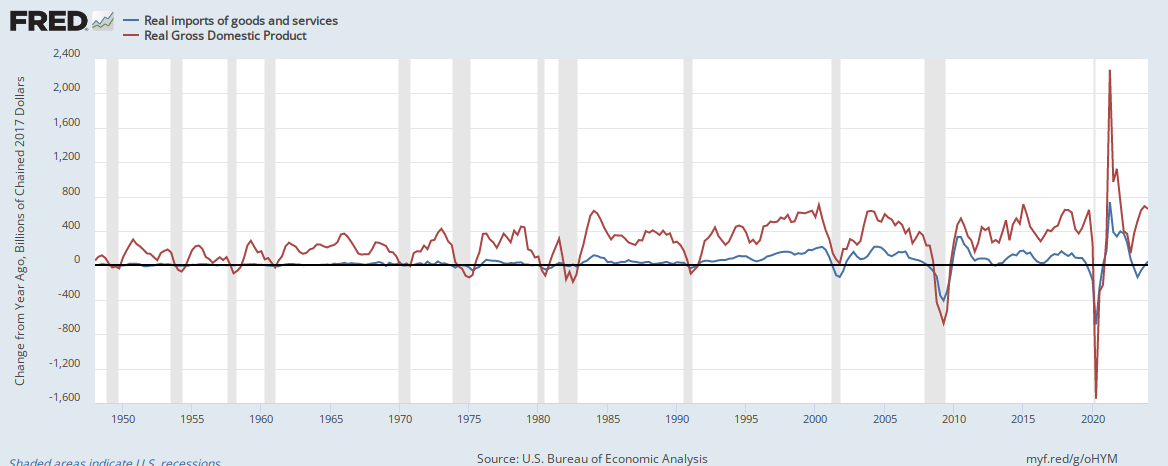

But I think that imports result in the export of our dollar, trillions of dollars of which are saved by foreign interests.

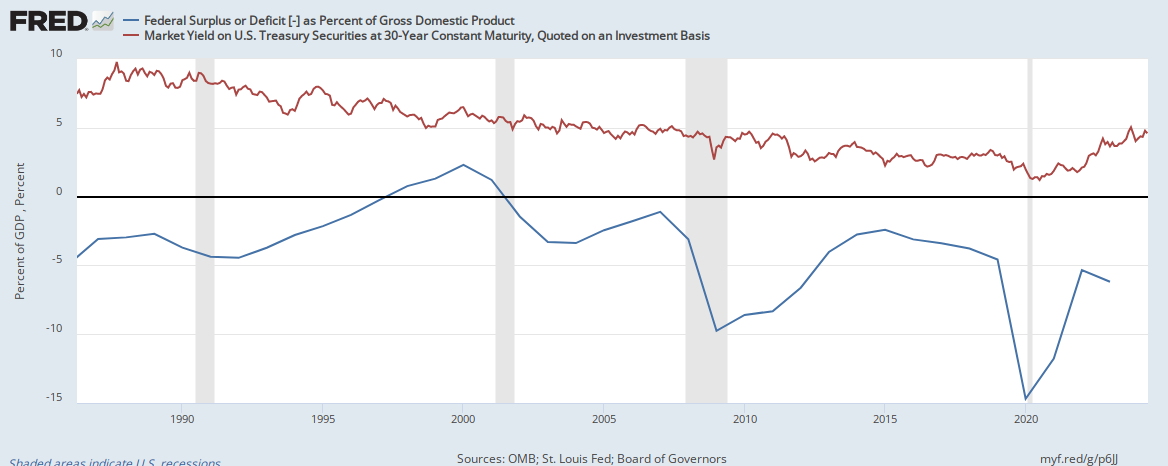

You can't cut out the mechanics behind the identity because they don't match the theory... savings = investment within the NIPA framework. All the identity tells us from imports > exports is that this differential will be used to fund subsequent investment. If there is a fiscal deficit, some of this imbalance will be lent to the public sector at the behest of the private sector. Sometimes this can be desirable. Sometimes it is counterproductive.

Point being, crowding out of private investment is a detriment to long term economic growth. This cannot be identified from within JFC's (or your own) framework.

Deficit spending/ debt is money that replaces the money that's currently "leaked" out of our economy.

Again... your definition of leakage doesn't fit within the framework. You can't pick and choose what aspects of the NIPA identity that are to adhered to and ignored at will.

...a lot of investment these days isn't productive. Speculating on real estate or energy removes as much money as it adds and does very little relative to the volume of money that moves through those markets to put people to work. Investment should be broken into subcategories IMO as not all investment is of the same quality.

Nobody has put forth the claim all investment is equal or yields equally productive/profitable returns.

I just think that imports create a fiscal problem that if misunderstood will cause an accounting problem that could be totally avoided if only we understood the nature of our currency.

What are these potential fiscal and accounting problems?