- Joined

- Sep 24, 2011

- Messages

- 38,317

- Reaction score

- 44,345

- Location

- Atlanta

- Gender

- Male

- Political Leaning

- Independent

Is there a published metric for units of production purchased by a specific unit of labor? I mean is that like a "thing"?

I brought this up in a earlier thread, and the idea was pretty much poo pooed, but the purchasing power of the median labor hour seems to be a much better metric than inflation for measuring our economic health. Is there a name for this? If not, can I claim the concept as my very own and get an award or something?

Anyone got a suggestion on what I should name this concept? Maybe PPPMWH (Purchasing Power Per Median Work Hour). Or 3PH for short? How about 3CPO, no, that conjures up images of a gold tin man.

Perhaps one way to go about this discussion is talk about what various economic indicators tell us, and why there is weight given to some economic indicators that perhaps grab more headlines than others that do not generate near the same degree of debate.

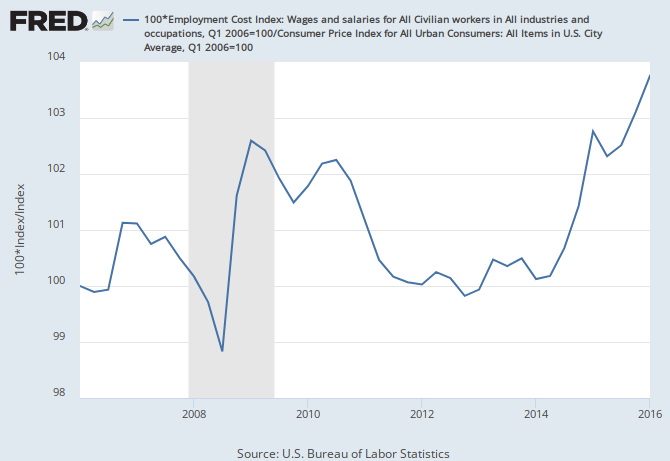

The issue at hand is what inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) or Personal Consumption Expenditures price index (PCE) really tells us *and* who is impacted. Without derailing the conversation too much on the difference in these measures or why the Fed prefers one over the other, the ultimate goal is to tell us in economics discussions what the typical basket of goods and services that we all buy cost on a trend line. The reason that is important is because by theory no one is immune from the impacts of inflation when measured on what we typically buy. As a key economic indicator it gives us some idea what the "cost of living" is when defining these basic goods and services. A secondary reason why it is important is in line with other key economic indicators it tells us the health of inflation when matched against income and wages, or matched against unemployment, or matched against currency strength, or matched against GDP all also on a trend line.

One thing we should dismiss is the idea that one economic indicator tells us the whole story about the status (or health) of an economy.

What you are asking for in "median labor hour" is something we already have in terms of what it tells us on the status of the workforce. Median household income on a tend line (for example) gives us a point of reference on the standard of living and distribution of income in an economic model. Because "median" anything gives us two halves to evaluate. A similar story is dealing with mean household income on a trend line as that gives us averages to evaluate the same thing (standard of living and distribution of income.) On that level we can dig deeper into various income quintiles and know how various demographics operate in the economic model.

The main reason why there is not much effort to blend into a single stat purchasing power (presumably using inflation measure) by the median labor hour (your term) is it clouds what these indicators tell us as they stand today.

When economists, the Fed, or the government, or whoever else look at these key economic indicators the whole idea of having so many is to identify economic fault. For instance, if inflation suddenly takes off but all other economic indicators (like unemployment, or GDP, or median household income) stay mostly flat that is something to evaluate. It is monetary policy, is it the dollar index, is it some problem with production or imports? We have a basis to evaluate why one stat becomes out of sync with others. Blending all of these things into various single stats may remove certain economic disparities we need to know about with all of these separate reports.

Let me close by saying the whole purpose of economics as an academia is to observe function and behavior. Inflation measures tend to upset people as some look at it as "unregulated taxation" or "theft of income," but those groups tend to ignore all the other economic indicators when doing so. Worse, they tend to ignore what the economics of the matter tells us about the difference between healthy and unhealthy inflation. All the numbers go into that evaluation and show us why we want a 2% inflation.

When engaging in looking at one number without any context, you get ... :scared: